EU-Central Asia Relations Unlikely to Change

Central Asia is not ready to expand ties with Europe, experts argue

Beiimbet Moldagali, Vlast, Brussels.

Читайте этот материал на русском.

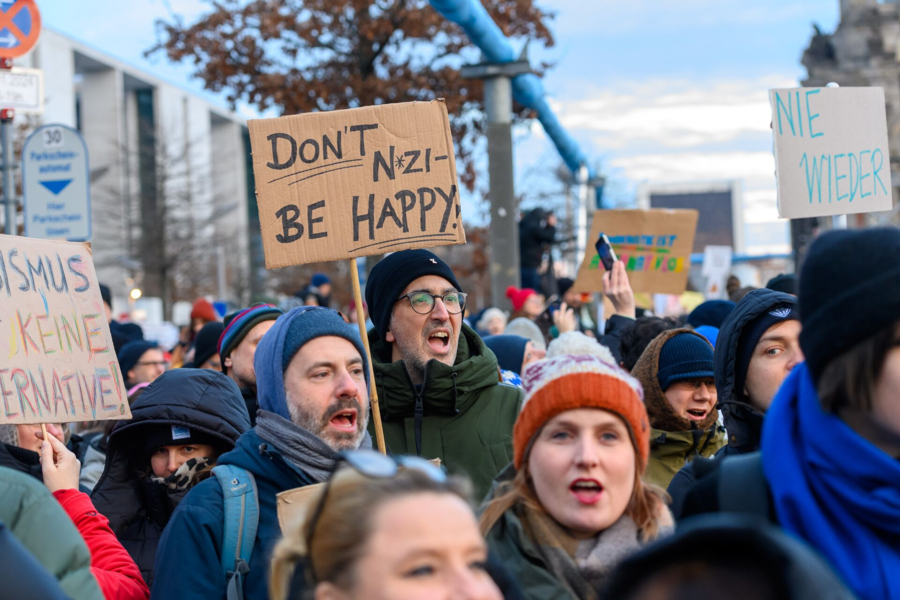

In early June, 27 countries in the European Union (EU) held elections that favored the centrists in the organization’s Parliament, despite a surge in support for Eurosceptic and far-right parties.

Vlast spoke with experts on how these results might impact the EU’s relationships with Central Asian countries , its policy towards Ukraine, and its future expansion process.

A Limited Role in Foreign Policy

The European Parliament and its elections are less influential on foreign policy than national elections, said Samuel Doveri Vesterbye, Managing Director of the European Neighbourhood Council. In fact, this is a role played mostly by EU member states, while the European Parliament mostly controls the EU budget.

The Parliament, however, can play a role by setting annual limits on the EU’s commitments in various policy areas.

"The European Parliament can influence EU foreign policy by blocking decisions, and they have done so in the past," Vesterbye told Vlast.

The opinion of the European Parliament is also important in shaping the EU’s political course, given that it is the only European institution that is directly elected by the people, said Tanya Marocchi, Director of the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum.

Marocchi expects that the majority of European Parliament members will continue to support financial, logistical, and military aid to Ukraine.

"Not all far-right parties are the same"

The far-right threat could change this course, although their influence has yet to materialize at EU level.

"More and more governments or coalitions include the far-right, such as Giorgia Meloni in Italy," Vesterbye said.

Marocchi warns that, despite its gains, the far-right should not be considered a unified bloc in foreign policy.

“Its two main parties — the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) and the Identity and Democracy (ID) group — hold different views. ECR supports Ukraine, while ID leans more towards Russia,” Marocchi told Vlast.

Vesterbye points to Hungary as a case where Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s right-wing government can sway EU policy.

"In Orban we see a leader who is more pro-Russian than pro-Ukrainian. He opposes LGBTQ+ rights, defends traditional values, and is less liberal. He is also changing the media landscape and creating problems in the judiciary. For years, he has influenced EU foreign policy and complicated the process of forming a unified course, particularly regarding Ukraine," said Vesterbye.

In Italy, conservative and Christian values are prevalent, Vesterbye argued, saying that while Prime Minister Meloni’s position aligns with EU foreign policy, her domestic policy diverges.

"Meloni supports European defense, the European industrial plan, and Frontex, which manages EU borders. She is pro-Ukrainian and pro-American, she signed major defense contracts with the US and follows the EU and the Commission’s policy. This shows that not all far-right parties are the same," said Vesterbye.

A great portion of the work of the European Parliament is to advocate for human rights, but the rise of far-right parties could change this, said Fabienne Bossuyt, associate professor of EU Foreign Policy at Ghent University.

"Of course, there are still several MEPs that are not right wing, and we expect them to protect human rights. But the balance could shift. Some far-right members, I would say, have ties to Russia. Therefore, I would expect them to be less critical of Russia, less openly supportive of Ukraine," Bossuyt told Vlast.

Central Asia: Limited Partnership and the Importance of Shared Values

In June, during a meeting with Central Asian journalists in Brussels, EU Foreign Affairs and Security Policy spokesperson Peter Stano said that the European Parliament election results would not affect EU relations with Central Asian countries.

"In our partnership, the sky is the limit. And the limit in this case is determined only by the desire of our partners, and on our side, by principles and values. We’ll go as far as our partners want to," said Stano.

He also added that all 27 EU member states are "determined to continue developing very strong relations with Kazakhstan as an important partner."

Kazakhstan is the EU’s closest partner in Central Asia, says Bossuyt. Kazakhstan was the first Central Asian country to ratify an enhanced agreement with the EU.

"I think this process will continue with the new compositions of the European Commission and the European Parliament. But I can also imagine that with more far-right MEPs, the European Parliament may become less critical of human rights compliance," said Bossuyt.

Marocchi also does not expect significant changes in EU-Central Asia relations. Despite the EU’s new strategy in 2019 and clearer priorities for the region, "they still focus on energy and connectivity."

Vesterbye believes that EU-Central Asia relations could reach a new level after the next EU expansion. Typically, after this, living standards and wages rise in new EU member states, making their energy and labor more expensive for European industry.

"Europeans will need new partners. For example, 20 years ago, German companies turned to Turkey, but now it has become more expensive. Germans might now look to Central Asia," said Vesterbye.

Marocchi disagrees, believing the potential inclusion of Ukraine, Moldova, and Georgia in the EU would not significantly alter the situation, because it will not create a direct EU border with Central Asia.

She adds that while there have been discussions about extending the Eastern Partnership to Central Asia, it has so far only resulted in inviting representatives from these countries to meetings within the annual work plan.

"Relations with Central Asia remain largely transactional in nature, and different from the discourse around engagement with Eastern Partnership countries, which is strongly focused on common values. This is a key difference, not to be discounted," concluded Marocchi.

European Expansion: Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova

On June 25, an intergovernmental conference in Luxembourg kicked off Ukraine and Moldova’s accession to the EU. Speaking on Ukraine, Belgian Foreign Minister Hadja Lahbib said that "the accession process [...] will be requiring a continued dedication to reforms in crucial areas like the rule of law, judicial reform, and a fight against corruption."

The war has made Ukraine’s EU accession inevitable, said Vesterbye. Before the war, Ukraine and Moldova had limited chances of joining.

According to Michael Emerson, senior fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies, the start of negotiations indicates that Ukraine and Moldova have met the preliminary conditions. However, their entry into the EU could take years.

"This is the beginning of a long process. In the case of Croatia, the most recent new member state, it took ten years from application for membership to actual accession," said Emerson.

Marocchi noted that the speed of accession depends on the authorities in Kyiv, Chisinau, and Tbilisi, as it is a process with specific methodology and rules.

"For Moldova, the results of the Presidential October elections will be telling. Ukraine so far has managed to advance steadily on the reform track while under the immense strain of resisting Russia’s war of aggression," she said.

Ukraine’s deputy Prime Minister for European and Euro-Atlantic Integration, Olha Stefanishyna, said that Kyiv would be able to complete all procedures and reforms to join the bloc by 2030.

The situation with Georgia is less clear: In the spring, the parliament, dominated by the Georgian Dream party, passed a so-called “foreign agents” law, sparking mass protests. The bill was dubbed the "Russian law" due to their similarities.

"The adoption of this law has greatly hindered the country’s progression on the enlargement track: Cracking down on civil society is not compatible with EU laws and values," said Marocchi.

Earlier in July, the EU representative in Georgia already announced that the country’s EU accession process has been halted due to the foreign agents law. The situation could change in the fall, when the country is due for parliamentary elections.

"If [the ruling] Georgian dream party is re-elected, it could be that there will be no progress towards opening the accession negotiation," noted Bossuyt.

Vesterbye is confident that in the elections, Georgians will choose a pro-European path of development.

"About 90% of Georgians want to join the EU. Most likely, in October, Georgians will vote against the current government in favor of a pro-European one that will be able to [resume] EU membership negotiations," said Vesterbye.

Власть — это независимое медиа в Казахстане.

Поддержите журналистику, которой доверяют.

Мы верим, что справедливое общество невозможно построить без независимой журналистики и достоверной информации. Наша редакция работает над тем чтобы правда была доступна для наших читателей на фоне большой волны фейков, манипуляций и пропаганды. Поддержите Власть.

Поддержать Власть